When Intelligence Becomes Abundant

How artificial intelligence is forcing a deeper question, not about what machines can do, but about what humans are for...

There is a particular kind of moment in human history where you can feel the ground shifting before anyone has language for it. It’s not loud at first. It does not arrive with a single invention, speech or crisis. But is almost a slow and persistent discomfort we feel. Old ways of organising life still technically work, but they feel thinner. Systems still function, but they feel strained. People still perform their roles; but they are less certain why those roles matter in the same way they used to.

Vaclav Havel (the last serving Czech president and activist) once described moments like this as periods where something is leaving, and something else is painfully being born. Not yet fully visible. Not yet fully understood. But unmistakably present in the atmosphere of a civilisation. People feel it before they can name it. Institutions sense it before they can respond to it. Language always arrives late to transitions like this.

I think there are good reasons for suggesting that the modern age has ended. Today, many things indicate that we are going thorough a transitional period, when it seems that something is on the way out and something else is painfully being born. It is as if something were crumbling, decaying, and exhausting itself, while something else, still indistinct, were arising from the rubble. - Vaclav Havel.

We may be living inside one of those moments now.

Not because artificial intelligence is impressive. Not because technology is accelerating. Those things have happened before. What feels different is that we are moving toward a world where competence which is; the ability to produce technically correct, usable, and often high-quality output, is becoming abundant. And when something that once defined status, identity, and economic value becomes abundant, civilisations tend to reorganise around whatever is still scarce.

Five hundred years ago, knowledge was scarce. Today, intelligence itself is starting to look less scarce than we ever imagined possible.

That does something profound to how humans see themselves.

What Havel was pointing to was not simply political transition. It was civilisational. The collapse of one way of understanding reality, and the uncomfortable emergence of another. Those periods are rarely neat. They are disorienting. They are full of contradiction. Old institutions continue to operate while losing moral and psychological gravity. New systems emerge before society fully understands what they are for.

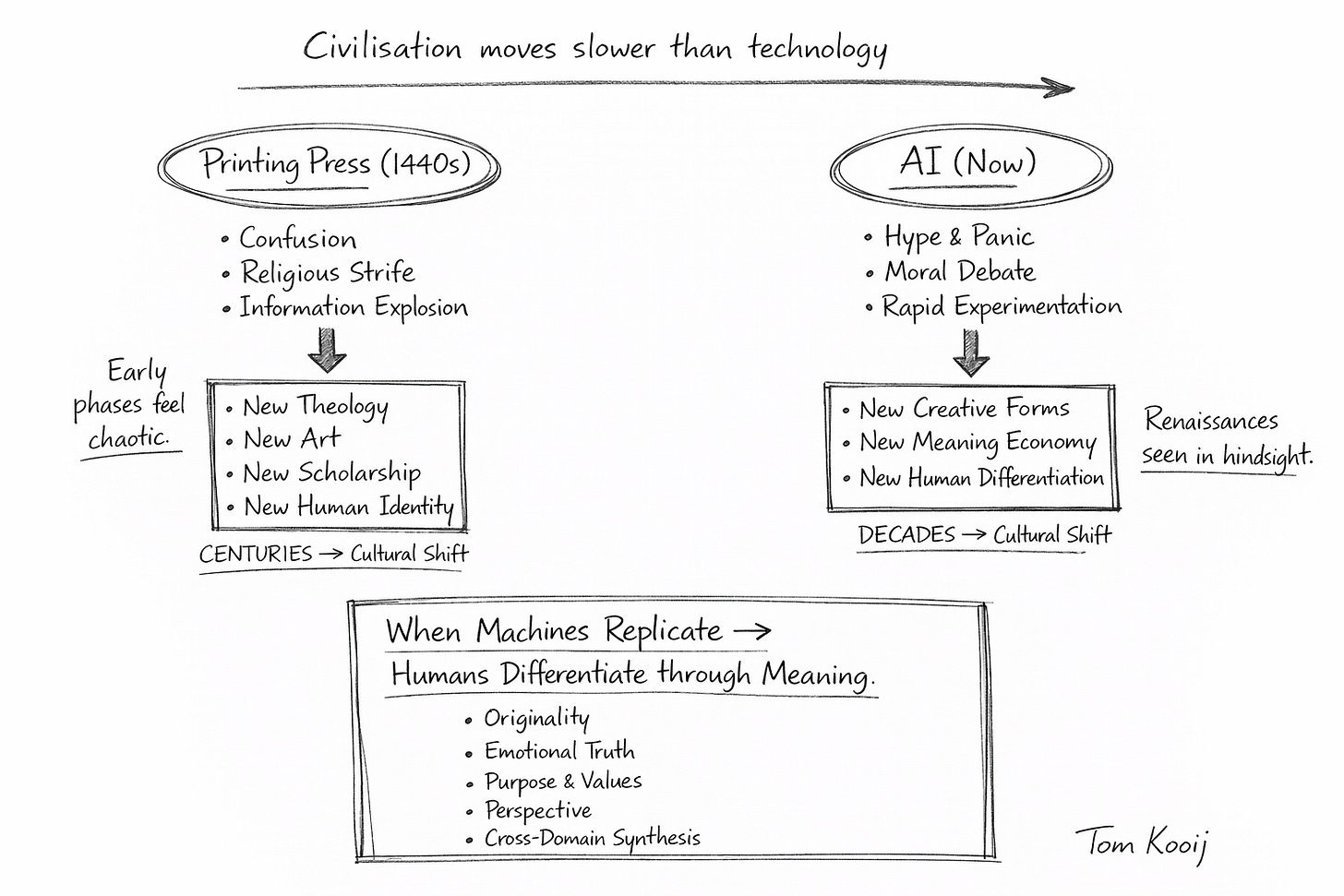

The Renaissance was one of those moments. The early Church Reformation was another. And there is a growing possibility that the early decades of the twenty-first century will be remembered in similar terms, not because of a single invention, but because of a shift in how humans understand knowledge, authority, and ultimately themselves.

When Abundance Changes What It Means to Be Human

The Renaissance is often told as a story of beauty. Of artists and thinkers and scientists suddenly emerging from darkness into light. The reality is messier and far more relevant to where we are now. The Renaissance was born from destabilisation. From trauma. From the collapse of previously unquestioned authority structures. The Black Death did not just kill millions of people. It broke labour systems and economic hierarchies. It broke the assumption that the social order was fixed and divinely protected (in the immediate sense). Entire regions were forced to renegotiate how life worked.

Then the printing press arrived and quietly redistributed power. It did not destroy institutions overnight. It eroded them and allowed alternative interpretations of reality to spread. We saw people outside formal authority structures participate in meaning-making. It lowered the cost of knowledge distribution so dramatically that it forced society to confront a new question: if knowledge is no longer scarce, who gets to decide what is true?

Today, artificial intelligence is doing something adjacent but deeper. It is lowering the cost of cognition. Not just storing knowledge. Not just distributing knowledge. But generating working versions of thinking itself. Drafts of strategy, writing or code. Drafts of design, analysis and of problem-solving pathways. It isn’t perfect, nor is it conscious or alive. But it is becoming increasingly competent.

So when competence becomes widely accessible, status, identity, values all shift on an individual level. Meanwhile, entire economic models not only shift but most importantly, cultural definitions of what makes a human valuable begin to change.

So when competence becomes widely accessible, status, identity, values all shift on an individual level. Meanwhile, entire economic models not only shift but most importantly, cultural definitions of what makes a human valuable begin to change.

We can all agree there is already a subtle but growing cultural anxiety around this. It shows up in economic fear, but underneath there is something more existential happening.

For most of the industrial and post-industrial era, many people built identity around what they could do that others could not easily replicate. The expert. The professional. The specialist. The person who had access to knowledge or tools or processes that were scarce.

When those things stop being scarce, humans start asking a deeper question. If machines can produce competent outputs across knowledge work, creative work, technical work, and analytical work, what is the human role that remains uniquely meaningful?

Historically, when a civilisation hits that question, it does not shrink. It transforms.

Look at the printing press…it did not eliminate scholars. It expanded scholarship, allowing ideas to move beyond universities into cities, churches, and public life. Theology did not disappear; it diversified, as voices like Luther and Zwingli who carried varying interpretations of truth and brought it into ordinary life at a scale history had never seen. Art was not diminished; it expanded, allowing new schools, styles, and regional expressions to emerge far beyond traditional patronage centres. Even authority itself was not removed. It was fragmented, contested, and redistributed across institutions, communities, and individual conscience.

Artificial intelligence may follow a similar pattern, but with a different focal point. If the printing press made knowledge abundant, AI may make first-draft intelligence abundant. And if first-draft intelligence becomes abundant, then second-order capabilities become scarce. Judgment. Taste. Perspective. Narrative coherence. Ethical reasoning. Cross-domain synthesis. Emotional accuracy. Meaning construction.

In other words, humans may move further up the stack of what creativity and intelligence actually mean.

There is a strong historical pattern we can see; when technical production becomes easier, conceptual creativity expands. Think about when photography emerged, it did not kill painting. It forced painting to become more expressive. Or when recording technology improved, music didn’t die. It expanded musical diversity. Even the internet, it did not eliminate writing. It multiplied voices, styles, and formats.

Artificial intelligence may do something similar but at a larger scale. It may remove technical barriers to creating. Which means more people can attempt to create and this means experimentation increases. So then we see, entirely new forms emerge, which is the definition of creativity itself evolves.

One of the most under-discussed aspects of this shift is the emerging idea of what I will call the, authenticity premium. So, when technically competent output becomes easy to generate, people start valuing things that feel unmistakably human. Not polished. Not perfect. But emotionally anchored. Story-driven. Identity-rich. Contextually grounded. Imperfect in ways that feel like someone real created this...

You can already see this in subtle signals. Handmade goods and local experiences increasing in perceived value. Story-based brands outperforming technically superior but emotionally empty alternatives. Even we see long-form personal writing building deep loyalty even in a short-form content world. Or despite digital networks available at the touch of a button, we see physical communities retaining meaning more than ever.

These are not random cultural preferences. They are early signals of a deeper economic and psychological shift.

Abundance changes what scarcity looks like. And scarcity drives value.

If design quality becomes abundant, taste becomes scarce. If writing quality becomes abundant, voice becomes scarce. If knowledge becomes abundant, wisdom becomes scarce. If intelligence becomes abundant, perspective becomes scarce.

And perspective is uniquely difficult to scale, because it is built from lived experience, integration of contradictions, and time spent wrestling with reality rather than simply processing information.

This is where the regional versus city dynamic becomes incredibly interesting in the AI era.

In the past, large global cities like New York and London have been places where talent, capital, and cultural influence concentrate. Not just in theory, but in lived reality, for example, these are places where major financial decisions are made before markets open elsewhere, global media narratives are shaped before they reach the wider world and where cultural signals are validated before they spread outward.

These cities thrive when information flow and network effects drive value creation. Ideas move faster because the people who generate them, fund them, regulate them, and communicate them are often within the same physical and social ecosystems. A conversation in a law firm can influence a capital decision. A capital decision can influence a media narrative. A media narrative can influence culture, politics, and market behaviour. Proximity compounds influence.

They are also optimised for speed, access, and global influence. If you need specialist knowledge, it is likely within a few degrees of separation. If you need capital, there are pathways. If you need legitimacy, there are institutions. If you need scale, there are networks designed to amplify quickly.

Sydney and Perth operate as scaled-down versions of that dynamic, with strong professional networks, institutional influence, and economic centralisation. They do not operate at the same global gravitational pull, but they still function as regional coordination centres, places where capital pools, where regulatory interpretation happens, where major commercial decisions concentrate, and where professional and institutional authority is reinforced through network proximity.

The historical advantage of these cities has never simply been size. It has been concentration. Concentration; of knowledge, of decision-making, capital allocation. and cultural validation. When these layers sit on top of each other, they create compounding momentum that is very difficult for distributed or regional environments to replicate.

But if intelligence and information become more evenly distributed through AI systems, some of the past advantages of large cities may flatten slightly. Not disappear. But change.

The advantage may shift from pure access to information toward access to meaning-making communities and lived identity ecosystems.

My thought is, cities like New York and London will likely double down on being global coordination hubs. They’ll continue to be places where large-scale capital flows, regulatory frameworks, global culture, and major institutional narratives are shaped. They may become even more concentrated in terms of influence. But they may also become more abstracted from lived human experience if digital cognition replaces large parts of professional execution.

Perth sits in a fascinating middle space. It has enough scale to attract capital, infrastructure, and professional ecosystems. But it still retains geographic and cultural connection to physical industries, resource economies, and place-based identity. That combination may become increasingly valuable in a world where purely digital economic activity dominates large parts of global markets.

Then there are smaller regional communities. Places like Denmark, WA. Historically, these places have been seen as peripheral. Lifestyle choices rather than economic centres. But so did renaissances, as they emerged from smaller, tightly networked environments where culture, capital, and experimentation could mix without being completely absorbed into massive institutional gravity.

Think of Florence (the birthplace of the Renaissance), it was not the largest city in Europe. But it was/is a dense network of capital, craft, philosophy, and risk-taking. Smaller ecosystems allow faster cultural experimentation because social networks are tighter. Feedback loops are faster. Identity is more place-anchored. Trust networks are more embodied. Physical presence still matters.

If AI makes knowledge and technical production portable, then, where people choose to live may shift from ‘where the jobs are’ toward ‘where meaning, identity, and life coherence exist.’

So, regional communities may then become more valuable as identity anchors in a cognitively abundant world. Places where people can build physical, relational, and cultural depth while still participating in global digital economies.

That does not mean regional communities automatically become innovation hubs. They still need network density, capital pathways, and cultural openness to experimentation. But the structural disadvantage may reduce.

There is also a psychological layer to this. Humans do not live purely in cognitive space. We live in embodied space. Physical environments shape identity, creativity, and emotional resilience. The more work moves into digital cognitive environments, the more people may crave physical grounding. Nature. Sport. Craft. Physical community. Local ritual. Local belonging.

Large cities will likely respond by becoming more experience-driven. More curated. More identity-focused and less about being purely functional. But smaller regional areas may have an advantage in providing coherent lived environments where digital work and physical life can coexist in healthier ways.

This may create a new kind of distributed renaissance network. Not one global centre. But multiple identity-rich nodes connected by digital infrastructure but differentiated by culture, place, and lived experience.

There is also a risk layer to all of this. Renaissances are rarely clean transitions. They are chaotic. The Renaissance period included religious wars, political violence, massive inequality, and information chaos. The destabilisation of authority structures creates opportunity but also creates fragmentation.

We are likely to see similar patterns. Truth becoming more contested. Identity becoming more tribal. Economic displacement creating social stress. Institutions struggling to maintain legitimacy. Cultural narratives fragmenting faster than they can be stabilised (ergo-USA)…

But historically, creative and intellectual expansion often happens inside that instability. Not outside it. Humans often become more creative when they are forced to reimagine how life works.

That said, the deeper shift happening may not be technological. It may be psychological. The next renaissance may be less about external artefacts and more about internal integration. Not just what humans can produce. But how humans interpret existence in a world where intelligence is no longer uniquely human.

Think about it, if machines can generate ideas, strategies, and outputs, then the human frontier may move toward deciding what is worth doing, what is worth building, and what is worth believing. That is not a technical skill. That is a philosophical, psychological, and cultural skill.

if machines can generate ideas, strategies, and outputs, then the human frontier may move toward deciding what is worth doing, what is worth building, and what is worth believing. That is not a technical skill. That is a philosophical, psychological, and cultural skill.

It requires integration of experience, emotion, ethics, context, and long-term systems thinking. It requires humans who can hold complexity without collapsing into simplification. It requires humans who can help others navigate overwhelming cognitive abundance.

There is a strong argument that the highest value humans in an AI-rich world will not be the fastest producers, but the clearest sensemakers. The people who can help others understand what matters inside a flood of possibility.

If that is true, then education, leadership, and culture will all shift. Not away from knowledge. But toward integration. Not away from skill. But toward judgment. Not away from productivity. But toward perspective.

This is where city and regional life may diverge in interesting ways. Cities may produce high-speed innovation cycles, high capital velocity, and large-scale institutional experimentation. Regional environments may produce deeper identity integration, long-horizon thinking, and more embodied forms of community and leadership.

Neither is inherently better. But the balance may shift. The future may belong to people who can move between both worlds. Who can operate in high-speed global cognitive networks while staying anchored in real physical communities, relationships, and place-based meaning.

Historically, the people who shape renaissance periods are not pure specialists. They are translators. People who can move between domains. Science and philosophy. Technology and humanity. Capital and culture. Data and lived experience. Strategy and identity.

We may see that archetype re-emerge. Not as a romantic ideal. But as an economic and cultural necessity.

There is also a time-scale reality that is important. Renaissances are not five-year technology cycles. They are generational transitions. The printing press was invented in the mid-1400s. The full intellectual, artistic, and cultural transformation unfolded over centuries.

We are likely in the early phase of something similar. Early phases always look like confusion, hype cycles, moral panic, and scattered experimentation. That is exactly what we see now with AI. That does not mean transformation is guaranteed. But it does mean conditions are historically familiar.

The real question is not whether AI will replace human creativity. The more interesting question is what forms of human creativity become more valuable because AI exists. If we look in the past, when machines handle replication, humans move toward originality, meaning, emotional truth, and cross-domain synthesis.

The frontier moves upward.

The greatest risk is not that humans lose creative capacity. The greatest risk is that humans outsource meaning-making. That we let machines not only help us produce, but help us decide what matters, what is true, and what is worth building. If that happens, civilisation becomes directionless.

Renaissances happen when humans reclaim authorship of meaning, not just production. They happen when humans realise the tools changed, and therefore identity, purpose, and cultural value must evolve too.

There is a quiet but powerful possibility that we are moving toward a world where being deeply, coherently human becomes a differentiator. Not performatively human. Not nostalgically human. But integrated. Self-aware. Context-aware. Capable of holding contradiction. Capable of building meaning for others.

If that is the direction, then the next renaissance will not be defined by a single technology or a single city or a single cultural movement. It will be defined by a shift in how humans understand themselves in relation to intelligence, meaning, and reality.

And if history is any guide, the people who help others navigate that transition, across cities and regions, across digital and physical worlds, across technology and identity will quietly shape the era, long before anyone gives it a name.

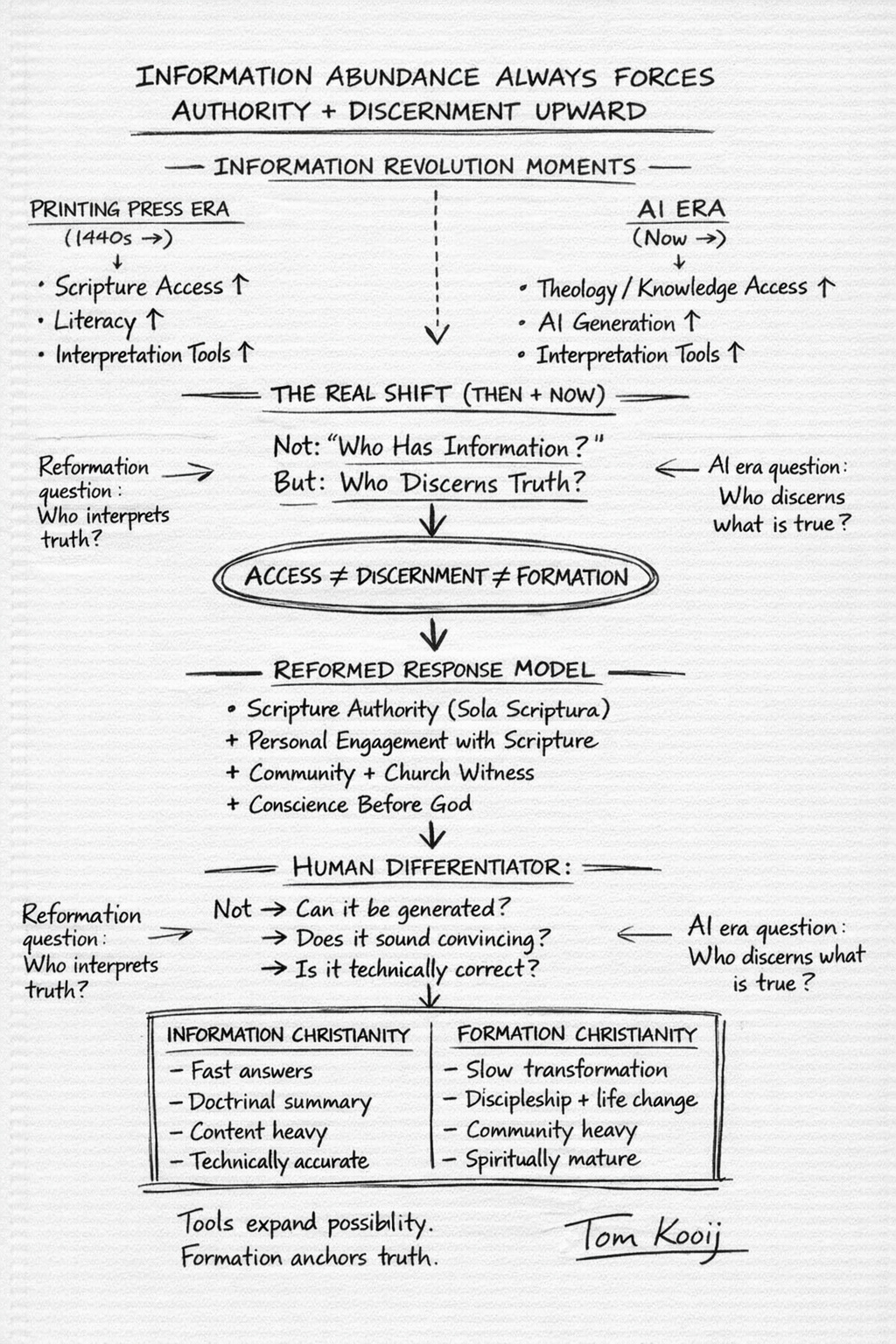

When Information Reshapes Truth and Authority

Another point, if this is truly a renaissance moment, is that it will not only reshape economics, creativity, and geography. It will reshape how humans understand truth, authority, and meaning itself. And if the past is anything to go by, whenever information becomes widely accessible, theology is one of the first domains forced to respond.

The Renaissance and the Reformation were not separate movements. They were entangled. The same forces that enabled artistic and scientific flourishing also destabilised religious authority and forced a re-examination of how truth was accessed and interpreted. When ordinary people gained access to scripture in their own language, something radical happened. Faith moved from institutional mediation toward personal engagement with text, interpretation, and conscience.

That shift was not primarily technological. It was existential. It forced believers to confront questions that had previously been answered for them. What does it mean to interpret truth responsibly? What does authority look like if it is not purely institutional? What does it mean to be accountable before God without institutional distance?

Those questions are not ancient. They are reappearing now in a different form. If artificial intelligence becomes a tool that can generate theological summaries, sermon outlines, doctrinal comparisons, and scriptural analysis instantly, then the question becomes less about access to knowledge and more about spiritual discernment. Not what can be generated, but what is true. Not what sounds convincing, but what is faithful. Not what is technically correct, but what is spiritually alive.

That is deeply aligned with Reformed thinking. The Reformation, particularly in its Swiss and later broader Reformed streams, was built on the authority and infallibility of Scripture (sola-scriptura) as the final standard for truth, not institutional power, while affirming that individuals are called to engage Scripture personally, yet never in isolation from community, accountability, and the witness of the church.

Figures like Zwingli lived inside information revolution conditions. He was working at a time when printed scripture and theological works were suddenly circulating far beyond traditional clerical structures. His life was not just about doctrinal positions. It was about navigating what happens when ordinary people suddenly have access to interpretive tools previously reserved for people who were perceived as '“institutional elites.”

The pressure he lived under was enormous. Political. Social. Religious. Cultural. He was not operating in a calm environment of theological debate. He was operating in a moment where entire societal structures were shifting. Cities were renegotiating authority. Rulers were renegotiating religious alignment. Communities were renegotiating identity. And inside that, he and others were attempting to anchor truth not in institutional continuity alone, but in scripture and in conscience before God.

If we translate that pattern forward, we may be moving into a world where theological literacy increases again, not because institutional religious participation suddenly spikes, but because information tools make exploration unavoidable. People will ask deeper questions because tools allow them to. But tools will not answer meaning. They will generate possibilities. Humans will still have to decide what is faithful, what is true, and what aligns with revelation and lived conviction.

From a Reformed evangelical lens, this is not primarily a threat. It is also an invitation to greater clarity. If the emphasis is on the authority of Scripture, the formation of the heart, life lived in accountable community, and transformation through grace rather than information alone, then artificial intelligence does not replace that work. If anything, it may expose the difference between faith that is merely informational and faith that is spiritually formed, embodied, and lived over time.

There is also a strong historical parallel around translation and accessibility. When Scripture moved into the language of ordinary people, the church did not disappear. It was forced to clarify what was essential. Some expressions fractured. Some deepened. Some became more culturally embedded. Some became more intellectually rigorous. Some became more personally and spiritually formative. The visible structures shifted, but the deeper work of the church, forming people around truth, grace, and transformed living, continued, often with renewed seriousness. The ecosystem did not collapse. It diversified, even as it was refined.

There is no reason to think an AI-driven information shift would not create similar diversification inside faith communities. Some will lean into automation of information. Some will lean deeper into formation, discipleship, and lived spiritual community. And historically, the latter tends to produce long-term resilience.

Bringing this down from the theological to the local and practical, you can already see early signals of renaissance-like shifts even in places like Perth.

One example sits inside professional services and advisory ecosystems. Previously, high-level strategy, legal thinking, financial structuring, and operational modelling required large teams and deep institutional infrastructure. Now, early adopters inside Perth’s professional ecosystem are already quietly using AI to collapse first-draft work. Research memos. Scenario modelling. Draft commercial structures. First-pass legal logic mapping. None of it replaces experienced judgment. But it radically changes how time is spent.

The emerging shift is subtle but important. Senior people are spending less time building raw output and more time interpreting implications, managing complexity, and advising on second and third-order consequences. The value is moving upward from production to interpretation and responsibility.

That sounds small, but it mirrors a Renaissance shift. When access to knowledge increased, the value moved toward interpretation and synthesis.

Another on-the-ground Perth example sits inside founder and operator culture. Early-stage founders who once spent massive amounts of time building pitch decks, early marketing content, or technical prototypes are now compressing those cycles dramatically. What that exposes is not technical capability gaps, but clarity gaps. The constraint is increasingly not “can you build it” but “should this exist,” “does this matter,” and “does this solve something meaningful.”

In real conversations inside Perth’s startup and operator ecosystem, you can already hear this language emerging. Less talk about tools. More talk about narrative clarity, positioning truth, and market meaning. Founders who have deep lived understanding of their customer and context are pulling ahead of founders who simply have technical build capability.

That again is a renaissance pattern. When production becomes easier, meaning becomes the differentiator.

Then if you move outside capital city environments into smaller regional ecosystems, the shift becomes even more interesting. In places like Denmark, WA, economic life has always been intertwined with physical reality. Land. Agriculture. Community reputation. Long-term relational trust. Multi-generational thinking. That kind of environment is less vulnerable to pure digital disruption because its core value is not just informational or cognitive. It is relational and embodied.

If AI accelerates cognitive work globally, regional communities may paradoxically become more valuable as places where identity, community, and meaning remain anchored in lived experience. Not in opposition to technology. But as a stabilising counterpart to it.

There is also a theological resonance here. Reformed evangelical thought places strong emphasis on vocation lived out in ordinary life. Faith expressed through work, family, community responsibility, and stewardship. Not purely through institutional religious structure. That worldview actually aligns strongly with a distributed renaissance model where meaning is lived locally but connected globally.

In that sense, small towns are not backward in an AI world. They may be early sandboxes/laboratories for what integrated digital and physical life actually looks like. Where global cognition tools are used, but identity is still formed through place, relationship, and lived accountability.

If you zoom back out, the theological parallel becomes even stronger. The Reformation was not simply about doctrine. It was about relocating authority. From institution alone to revelation plus conscience plus community. That did not remove structure. It redistributed responsibility.

AI may be forcing a similar redistribution. Not of spiritual authority, but of intellectual authority. If everyone has access to tools that can generate convincing explanations, then authority moves toward those who demonstrate wisdom, character, discernment, and consistency over time.

That is deeply aligned with biblical leadership models. Character before platform. Faithfulness before scale. Fruit over performance. In a world flooded with generated intelligence, humans may increasingly look for leaders who demonstrate integrated life, not just intellectual performance.

Historically, early church leaders who survived massive cultural shifts were not always the most technically brilliant communicators. They were often the most anchored. The most coherent. The most willing to live out their convictions under pressure. That pattern may repeat culturally in a non-religious sense as well. People may increasingly trust voices who are visibly grounded in lived reality rather than purely digital performance.

There is also one other sobering parallel worth acknowledging. The Reformation period was not peaceful. Information democratisation destabilised political and religious systems. It produced reform, but also conflict. It produced theological renewal, but also fragmentation. The same tool that allowed truth to spread also allowed error and extremism to spread (again, consider what we are seeing in the USA).

There is no reason to assume AI will be different. The same systems that allow wisdom to scale will allow confusion to scale. The same tools that allow truth exploration will allow persuasive falsehoods to proliferate.

There is no reason to assume AI will be different. The same systems that allow wisdom to scale will allow confusion to scale. The same tools that allow truth exploration will allow persuasive falsehoods to proliferate. Which again shifts value toward discernment, community accountability, and long-term trust relationships.

The Kind of Humans This Era Will Demand

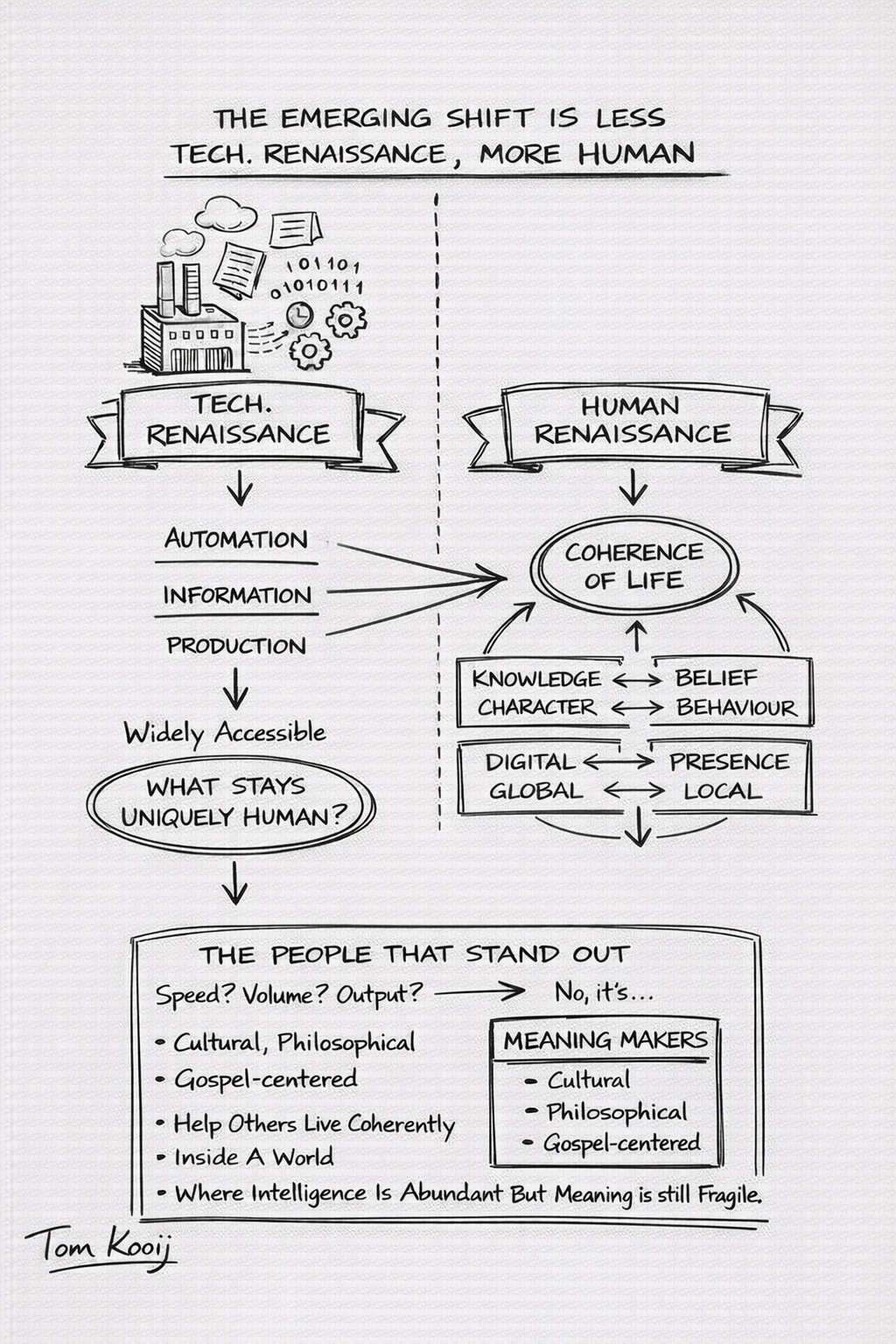

If you take all of this together, the emerging picture is less about a technological renaissance and more about a human one. Not because technology becomes less important, but because it forces a clearer question about what remains uniquely human when intelligence, information, and production become widely accessible.

What begins to matter more is not what we can produce, but how coherently we can live. How well we integrate knowledge with character, belief with behaviour, digital capability with physical presence, and global awareness with local responsibility.

That shift is not purely economic. Traditionally, renaissances reshape how humans understand truth, identity, purpose, and responsibility long before they are remembered for art, science, or technology. They change what a society expects a person to be.

Which means the people who shape this era are unlikely to be defined by speed, volume, or technical output alone. They will be the people who help others live coherently inside a world where intelligence is abundant but meaning is still fragile. That is not just an economic role. It is cultural. Philosophical. And ultimately grounded in truth that reshapes lives, not just ideas.

This moment will not ultimately be defined by artificial intelligence, or by any single city, institution, or industry. It will be defined by how humans respond to the responsibility that abundance creates.

This moment will not ultimately be defined by artificial intelligence, or by any single city, institution, or industry. It will be defined by how humans respond to the responsibility that abundance creates.

History shows that when tools radically lower the cost of knowledge or production, civilisation is forced to confront deeper questions about authority, meaning, and identity. The printing press multiplied books, but more importantly, it forced humanity to wrestle with who interprets truth. Artificial intelligence is multiplying intelligence-like output, and in doing so is forcing a similar confrontation around what intelligence is actually for.

The defining tension of this era is not access to AI. It is depth of judgment. Whether efficiency becomes the goal, or whether meaning, responsibility, and coherence continue to anchor decision-making. Whether humans are gradually shaped by their tools, or remain the ones deciding what those tools are ultimately for.

This tension will not resolve in one place. Cities will continue to matter because coordination, capital, and scale matter. Regional communities will continue to matter because identity, place, and lived accountability matter. The future is likely to belong to people and communities who can move between both without losing their centre, those who can operate inside global systems while remaining anchored in local reality, and who can hold complexity without surrendering clarity.

The theological parallel is not accidental. Periods of information upheaval have previously pushed belief away from inherited certainty and toward lived conviction. Not abandoning structure, but inhabiting it more intentionally. Not rejecting authority, but testing it more rigorously against truth, character, and fruit over time. As intelligence becomes more widely accessible, authority increasingly settles with those who demonstrate integrated lives, not simply impressive output.

The deepest renaissance shifts are never purely technological. They are anthropological. They redefine what a human is expected to be. The last great renaissance elevated the individual mind. The next will likely elevate the integrated human, intellectually capable, morally anchored, relationally accountable, and able to create meaning inside overwhelming complexity.

The real danger is not that machines become more capable. It is that humans become less intentional. Tools designed to assist thinking can slowly replace reflection, discernment, and responsibility if left unexamined. Civilisations do not struggle because tools become powerful. They struggle when humans stop deciding what power is for.

The opportunity of this moment is not simply to learn new tools. It is to become the kind of people who can hold truth, complexity, and responsibility in an age where intelligence is no longer scarce. The kind of people who can help others navigate a world where almost anything can be generated, but meaning still has to be lived, chosen, and built in community.

The second renaissance will not be led by those who can produce the most. It will be led by those who can see clearly, choose wisely, live coherently, and help others do the same. History suggests that these people rarely announce themselves. They simply begin, quietly and steadily, to shape the era around them.

TK